Winning the Power Wars

![]()

![]()

I wrote this posting on March 27, 2010, during Earth Hour. The lights were on.

Consumer electricity rates are something of a cash cow for electric utilities and especially for the governments who regulate them. Unlike direct taxation — increases in which are becoming decidedly toxic to the politicians responsible for the wealth grabs in question — incremental increases in the monthly electricity bills of harried, attention-depleted consumers typically go unnoticed. In many cases, this can be attributed to most consumers of electricity being of the opinion that there’s little they can do about their bills, short of making Earth Hour a daily event.

Of late, the people who manage power generation utilities have begun to appreciate that the environmental issues that drive greenwash like Earth Hour, far from being a threat, are a public-relations blessing sent from on high and delivered by FedEx. Unless the people who run your power company are all dead or living in a time warp, you’ll no doubt have noticed that they’re leaning on you to conserve power.

This seems a bit like General Motors leaning on its customers to buy fewer cars. In fact, it’s not, because the business model of General Motors and that of a power utility are conspicuously different.

There are, in fact, three distinct reasons for your electric bills including stuffers that encourage you to use less electricity – and perhaps even some degree of purported assistance to further your doing so.

- Power generation facilities – be they gas-fired power plants, nuclear reactors or fields of wind turbines – are expensive. Fully utilized – that is, installed in jurisdictions where all of their generating capacity is being paid for – they’ll produce a substantial profit. However, building a generation facility to address incremental increases in power consumption means that the power company responsible for signing the check for one of these puppies isn’t going to see it fully utilized for years. Most such utilities would rather see you use a bit less power, allowing them to forestall paying for increased generator capacity.

- In most places, power is sold at a fixed rate or at a small number of fixed rates depending upon the time of day in which it’s consumed. It’s purchased by the utility responsible for providing it, however, at a fluctuating market rate, which can get disturbingly astronomical during times of peak demand. Persuading their customers to curtail their demand for power during these peak periods will mean that electric utilities can avoid paying serious bucks to buy it when they can’t bill serious bucks to their consumers.

- The politics of electricity rates is a somewhat larger issue than the technology involved in creating the power being billed for in many places. Power companies and governments which encourage conservation often do so with the comforting knowledge that few of their customers will be motivated to do anything about it. If you complain about the increasing magnitude of your utility bills, they’ll be able to throw up their hands and say, in effect, “we tried to help you conserve power and lower your bills, but you ignored us. You have no one to blame but yourself.” This ignores, for the most part, that acceding to the conservation measures in question often involves serving dinner at 10:00pm, doing your laundry at four in the morning and generally freezing in the dark.

Nobody really wants you to reduce your energy consumption to save you money.

The most recent piranha to be tossed into the swimming pool of power rates is “time-of-use” pricing and the “smart” meters that implement it. Back in the day, power was simply metered in bulk and billed at a fixed rate. However, because electric generation utilities have to pay more for it at peak times, they’d like to be able to charge more for it during peak times as well. A smart meter records not only how much power you use, but when you use it.

In isolation, time-of-use pricing could be seen as just and fair. It ignores a number of ancillary issues that most power companies would prefer you ignored too, however:

- While time-of-use pricing tracks the real price of power to some extent, it’s still a pretty funky pricing structure. It penalizes the consumers of power for using it during the times when most people are likely to be awake, but it doesn’t pass along any market economies to the end users of power. If everyone reduces their consumption of electricity on a hot afternoon in July, for example, the spot price of power will drop. Your power company will still bill its time-of-use customers at its peak rate, and it will cheerfully pocket the difference.

- Power company management are often paid bizarrely high salaries, especially considering that they manage a public utility which does the same thing every day, and which enjoys a virtual monopoly. The president and CEO of Ontario Hydro, which supplies us with power – when it’s working – took home a base salary of $924,436.94 in 2009, according to the Ontario Ministry of Finance web page. The CEO of Ontario Power Generation, which manages the provinces power generating hardware, was paid $1,011,334.21 in 2009… plus an additional $31,232.91 in benefits. The page lists hundreds of additional staff – including several plumbers – who enjoyed six-figure salaries. This compensation was funded, needless to say, by the electricity rates of Ontario Hydro’s customers.

- Large industrial customers of power utilities typically pay much lower prices for power than do small consumer accounts. Power companies liken this to buying in bulk – if you were to approach General Motors looking for a few hundred automobiles, perhaps to supply a car rental company, GM might well sell them to you for substantially less than a single car would cost from a dealer. From the perspective of a car manufacturer, such a transaction would entail none of the usual costs of selling a single car, and they’d likely be prepared to pass those saving along to someone prepared to drive off the lot on hundreds of tires all at once. The situation isn’t actually comparable to selling power, as it costs the same to generate electricity no matter where it’s going, and essentially the same to transmit it, all other things being equal. In most jurisdictions, residential customers subsidize the rates of industrial users. Governments typically like this sort of arrangement, as it precludes large industries – with large numbers of employees paying large mountains of tax – from departing for somewhere with more competitive electric rates. You may feel differently, in the event that you find yourself chipping in for the power used by a business you have nothing to do with.

- Most notably, while time-of-use pricing can be made revenue neutral – that is, it need not increase your monthly electric bill – you’d have to make some highly visible changes to your lifestyle for this to happen. The people behind time-of-use pricing are betting that you won’t. In effect, they have very little to lose in implementing it – in most places, the power companies who roll out smart meters charge their customers a rental fee for them or compel them to pay for the new meters outright, ensuring that their ultimate out-of-pocket costs for the upgraded technology will be minimal.

Destructive Compliance

In a perfect world, electric utilities would charge just enough to offset their costs – that would be their real costs, excluding hundreds of top-level mandarins taking home more than a successful brain surgeon. Look around… this isn’t a perfect world.

At times, I dream of the day when our local power company sinks some really enormous buckets of money into smart meters, new generating capacity and perhaps even some power lines that don’t come down every time the wind blows… and we then cover the roof in solar panels and tell them to come and disconnect us from the grid. In the mean time, we’ve had to content ourselves with somewhat simpler technology.

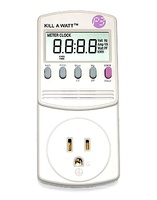

The device illustrated at the beginning of this post is a Kill-A-Watt meter. It costs about twenty-five dollars, and is available at most hardware stores. Used intelligently, it will visit sleepless nights, sweating palms and weekly therapy sessions upon the unworthy heads of the management of your local power utility. Specifically, it will let you target your electricity consumption and trim your power bill, often without making any serious changes to the way you live.

It will let you give them what they purport to want, and that which they secretly dread.

A Kill-A-Watt meter will tell you how much power anything plugged into it draws, and how much power said devices draw over time. It will also display your exact line voltage – which is of abstract interest if you think your power company is browning you out – and your exact line frequency, which is useful if some of your electric clocks seem to be running fast.

You can use a Kill-A-Watt meter to determine which devices in your home are really sucking back power, and as such, where best to apply some strategy in the furtherance of putting the beasts on a diet.

Here are a few examples:

- Desktop Computers: Plugged in and left that way, desktop computers – and their ancillary monitors, printers, modems, speakers, external hard drives, music interfaces, iPod docks and USB hubs – draw power all the time, even when they appear to be switched off. Modest but constant power draws like this can place a substantial thumb on the scale of your power bill, and they do you little good. While not all such devices should be powered down after hours – you’ll probably want to leave your FAX machine and your cordless telephone powered up 24/7 – a strategically-located switchable power bar can be used to disconnect much of your technology when it’s not required. Most desktop computers can be configured to automatically power themselves up as soon as their power bars are switched on. Hit F2 while your computer is booting to access its BIOS setup screen, locate the Power Management section and enable Power Up After AC Interruption.

- Game Consoles: Video games are actually powerful computers, typically with substantial processors that use wicked amounts of power. While running one for an hour or two each day isn’t likely to add another digit to your power bill per se, leaving these devices powered up all the time – to avoid saving games, for example – can get expensive. Some of them are substantial power vampires when they’ve been shut down, too, and can benefit from the introduction of a switched power bar.

- Programmable Dishwashers: Here’s one that won’t entail the use of a Kill-A-Watt meter. Most contemporary dishwashers have multiple cycle options, all of which sound like they’re worth enabling. Ours offers, among other things, a wash cycle, a sterilize cycle and a drying cycle. With all these cycles on line, the machine runs for almost two hours, and it fires up a huge electric heater the whole time. Our dishwasher got so hot for so long that it kept melting its cutlery basket. A few seconds of calculator action suggested that this appliance required some rethinking. Having washed its dishes in scalding water, there seemed little further benefit in further sterilizing them in more scalding water. As the dishwasher begins washing at 11:00pm at night and typically isn’t emptied until 9:00am the next morning, the dishes need not be dried – they largely dry themselves. Unselecting the latter two cycles pruned our monthly power bill by over ten dollars.

- Other Technology: There’s a lot of other technology that sucks back power when it purports to be sleeping, and this is where you’ll want to warm up a Kill-A-Watt meter to determine which of your toys should be mechanically switched… lest all your electricity savings find themselves diverted to the bottom lines of power bar manufacturers. Our huge glass-tube television, for example, seemed a likely power vampire – the Kill-A-Watt meter showed it drawing less than a watt when it was off. By comparison, one of the house bookshelf stereos drew twelve watts in standby, only slightly less than it swallowed when it was in operation. Measure everything.

- Air Conditioners, Refrigerators, Water Coolers and Freezers: Refrigerators and other devices that make things cold don’t run all the time, and you’ll want to plug them into a Kill-A-Watt meter for a day or two to see how many kilowatt-hours they consume over time. We were disturbed to learn that the tiny bar fridge in our basement outstripped our very much larger – and albeit, quite a bit newer – kitchen refrigerator. We came to appreciate that we were essentially renting the bar fridge for about ten dollars a month, or paying more for its electricity each year than we’d originally paid for the fridge. We subsequently came to appreciate that we didn’t really need a bar fridge. You can use this aspect of a Kill-A-Watt meter to compare the actual cost of running your existing refrigerator with the projected energy consumption of a new one, to determine when it’s worth upgrading these appliances.

- Coffee Makers: Coffee makers use a lot of energy to brew coffee, and then a somewhat smaller gulp to keep it warm. However, if you leave your coffee maker on all day, you’ll be truly shocked to learn what it’s costing you to run the beast. This is another useful application of the Kill-A-Watt meter’s consumption-over-time function. We ultimately determined that a pod coffee maker is cheaper to run, in that it brews a cup of coffee and then shuts down. The coffee pods for these things are a bit pricey, but they more than pay for themselves in power costs.

We’ve also unveiled a surprising number of power vampires in cordless devices that stay plugged in all the time, even though they’re rarely used; sundry innocuous radios; a rather unattractive table lamp that came on whenever someone touched it and various rechargeable garden implements. Older devices are usually less reluctant to waste power, and anything that feels warm is a likely culprit.

Automatic electric timers can also help nuke your power bill. Most homes have a number of things that don’t need to be powered up all the time. Air exchangers and humidifiers, for example, can be safely powered down while you sleep. Installing a timer for your hot water tank can save a lot of power, as long as long as you schedule your dishwasher appropriately and you don’t sleep walk to the shower at three in the morning.

A Kill-A-Watt meter, a few power bars and a deep and reverberant dislike for Ontario Hydro and all who sail in her have allowed us to reduce our monthly electric bill to about half its former immensity. Admittedly, this promises to be offset to some degree by several pending rate and tax increases later this year. On the other hand, the work of our Kill-A-Watt meter isn’t done yet.

As an aside, successfully conserving power can have unanticipated consequences. In 2007, Toronto Hydro – thankfully, not our power company – applied for a 6.3 percent rate increase on the grounds that its customers had responded to its repeated urging for conservation, and it’s billing revenue had declined by about ten million dollars. The rate increase was about equal to the average savings enjoyed by its customers as a result of their efforts to use less power – unplugging their computers and upgrading their refrigerators had accomplished precisely nothing.